What Is the Triple Screening?

Written and verified by the nurse Leidy Mora Molina

From the beginning of gestation, doctors begin to evaluate some aspects of the baby that may suggest the possibility of genetic diseases. One of the strategies implemented for this purpose is the triple screening or tripel test.

This study seeks to establish the risk of the baby having Down syndrome, Edwards’ syndrome, or Patau’s syndrome. Are you interested in learning more about this prenatal test? Keep reading, we’ll tell you all about it below.

What does the triple screening consist of?

As we’ve already mentioned, the triple screening or triple test is a routine complementary test in the first trimester of gestation.

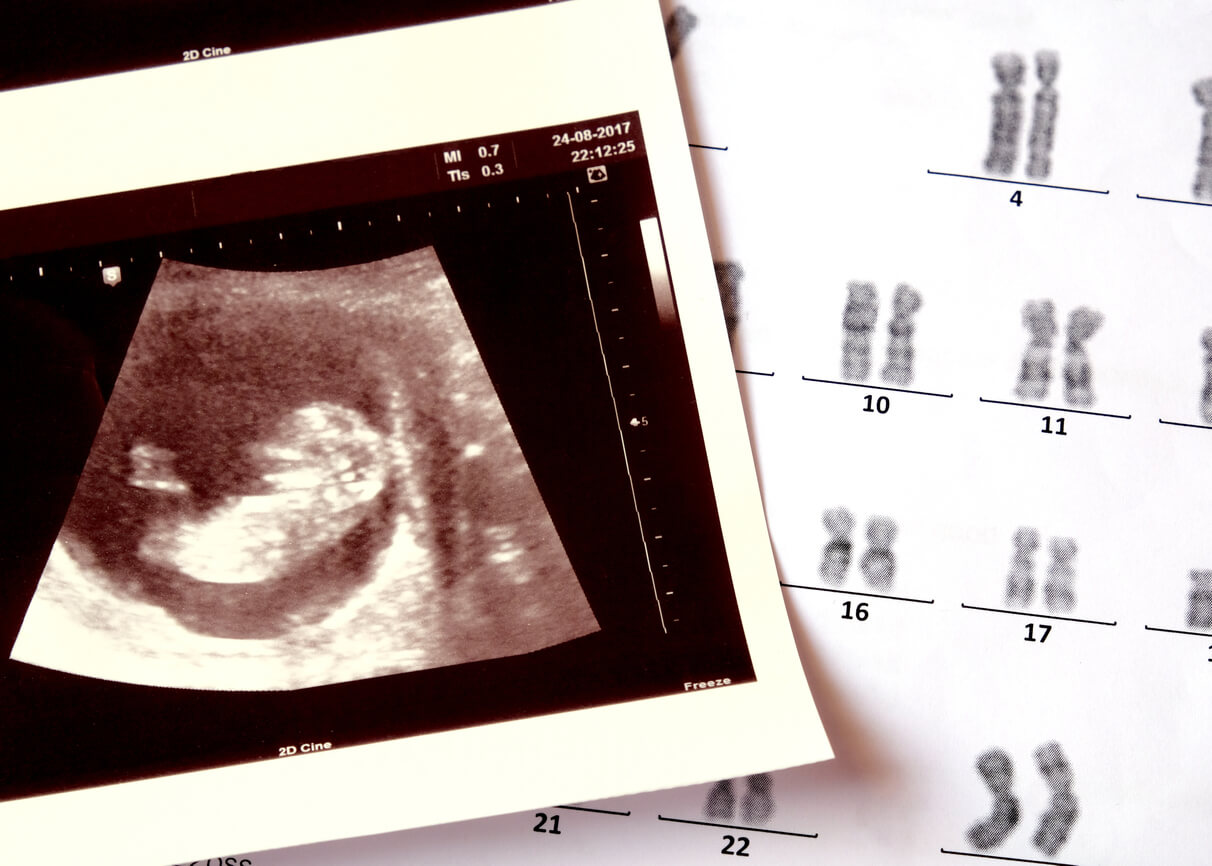

The objective of this test is to establish the mathematical probability that the baby being born has one of the most frequent genetic diseases: Down syndrome (trisomy 21), Edwards’ syndrome (trisomy 18), or Patau’s syndrome (trisomy 13). It also evaluates the presence of defects in the neural tube, which is the precursor structure of the brain and other organs of the nervous system.

This screening combines three different strategies:

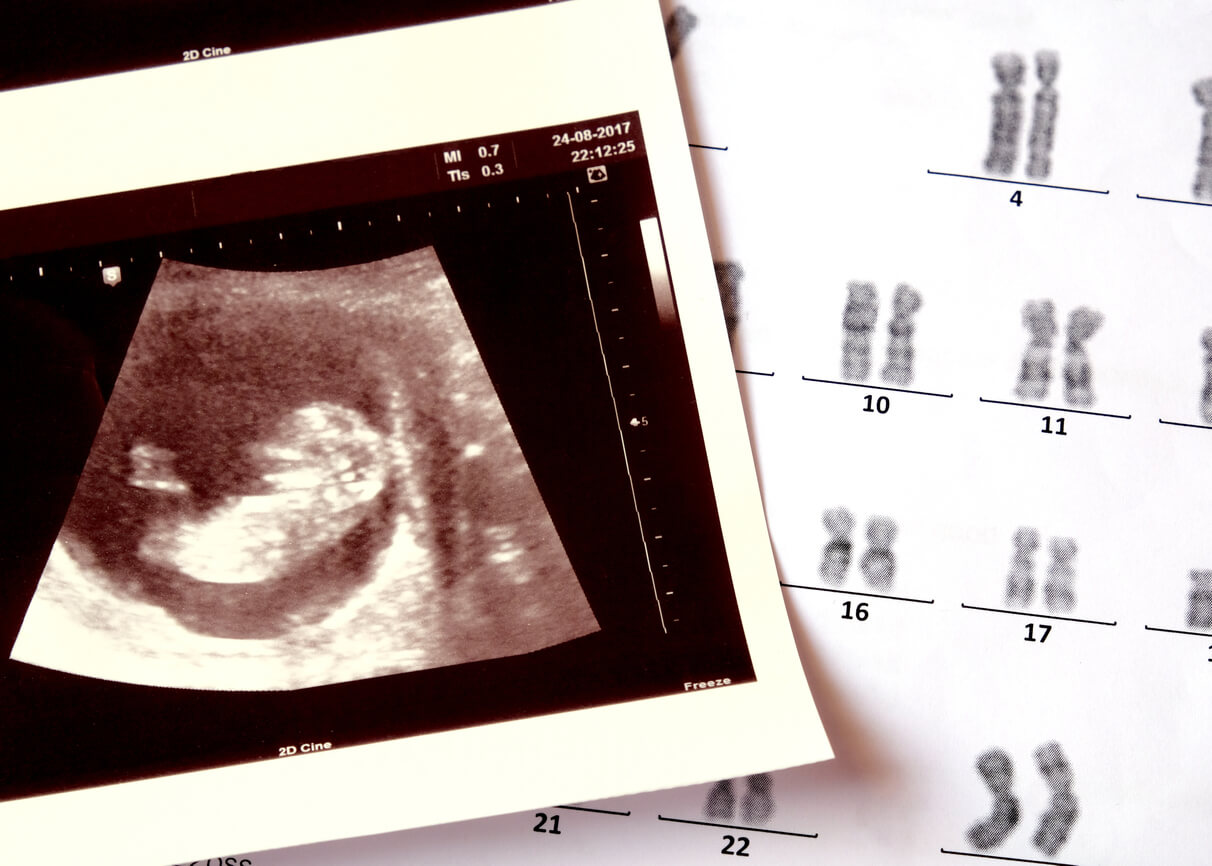

- Ultrasound study of the baby. Specifically, the measurement of the nuchal fold or nuchal translucency study.

- The determination of specific biochemical markers in maternal blood.

- Analysis of the mother’s demographic data, such as age, weight, and ethnicity, among others.

Once the information has been collected, the physician enters the data into a computer to determine a percentage risk of suffering from the aforementioned diseases. In other words, it doesn’t make a diagnosis of certainty of any of them, but rather alerts about the high or low probability of having them.

Although this test isn’t conclusive, its results are quite indicative. In the case of Down syndrome, the test is accurate in more than 95% of cases and its false positive rate is 4%. In other words, up to 4 out of every 100 fetuses considered to be at risk for the disease don’t have it in the end.

For this reason, when faced with a report of a high risk of fetal genetic disease, the physician proceeds to perform a confirmatory and invasive study, such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling. Both tests have a degree of diagnostic certainty of 99%.

When is the triple screening performed?

The triple screening is indicated between 11 and 14 weeks of gestation because this is the optimal period of reliability. Although it can be performed beyond the 15th week, it’s important to know that the diagnostic sensitivity decreases considerably with time.

All women, regardless of their history, are candidates for this study.

What is assessed in each test of the triple screening?

Here, we’ll tell you what is analyzed in each of the screening tests and how so that you can understand why they are so important.

1. Determination of biochemical markers in maternal blood

Through a maternal blood sample, specialists analyze the values of some hormones that may suggest an alteration in the number and distribution of the baby’s chromosomes. For example, alpha-fetoprotein (PAPP-A), human chorionic gonadotropin (free beta-HCG), and estriol. In some cases, inhibin A is also assessed and the study is called a quadruple test.

When there’s a genetic problem, these hormones tend to be altered. In Down syndrome, PAPP-A tends to be decreased and beta HCG elevated.

2. Abdominal ultrasound with measurement of the fetal nuchal fold

The second component of the combined screening is to evaluate the nuchal translucency, which is a fluid space at the back of the baby’s head. In general, in babies who have a genetic abnormality, this tends to be thicker than in those who do not.

In addition, the specialist will measure the length of the baby, which is indicated as the cranial-caudal length (CRL).

3. Analysis of maternal demographic data

The two parameters mentioned above are “crossed” in a computer along with certain information about the mother: Her age, her weight, the number of fetuses she’s carrying, her race, and her pathological history, among others.

It should be noted that not all women have the same degree of risk of carrying a fetus with a genetic disease. Below, we’ll tell you who is more likely to have a baby with these conditions:

- Women over 35 years of age.

- People with a family history of Down, Edwards, or Patau syndrome and other genetic anomalies.

- Pregnant women with a history of miscarriages or babies with congenital malformations.

- Pregnant women who’ve been exposed to environmental factors that increase the risk of a genetic alteration, such as exposure to ionizing radiation.

How are the test results interpreted?

As we mentioned above, this test isn’t diagnostic, but rather establishes the risk or probability of suffering from some specific diseases. Therefore, the results are indicated with a numerical value (as a fraction) and not with a “positive” or “negative”, as with other evaluations.

For example, if the result is 1/750 or 1:750, it means that the chances of carrying a baby with Down, Edwards, or Patau syndrome are 1 in 750. If we took 750 women with similar baseline conditions and similar blood and ultrasound results, only one of them would give birth to a baby with one of these diseases.

Now, is this risk high or low? Is it worrisome or not? As you’ll see, the interpretation of the results can be somewhat confusing for a mother. Therefore, it’s best to discuss the reports with the specialist, who’ll be able to give you the explanation you need.

In general, laboratories have established parameters to define high, moderate, or low risk and usually take into account the following values:

- Greater than 1/270 is considered a high risk.

- Between 1/270 and 1/1000 is considered an intermediate risk.

- Less than 1/1000 is considered a low risk.

If the pregnant woman receives a triple screening report with a high risk of fetal genetic disease (1/270; 1/150; 1/100…), an accurate diagnostic test, such as amniocentesis, should be performed.

Confirmatory testing

When screening is positive, it’s important to proceed with more specific, more complex, more costly, and more invasive evaluations:

- Fetal DNA test in maternal blood: Chorionic villus sampling: This procedure is performed when a detailed analysis of the baby’s DNA is required in order to detect other genetic diseases or to confirm/rule out the presence of Down’s, Edwards’, or Patau’s syndrome. This requires taking a blood sample from the mother and sending it to a specialized laboratory.

- Amniocentesis: This test is more invasive than the previous one and is reserved only for cases in which it’s justified, as it’s not risk-free. It consists of taking a sample of amniotic fluid through a puncture of the sac that houses the baby.

- Chorionic biopsy: Chorionic villus sampling: like the previous one, this is an invasive test and consists of taking a sample of the chorionic villi from the placenta. It’s performed by means of a puncture of the mother’s abdomen in order to study the baby’s DNA.

Some final considerations on prenatal studies

Screening tests are performed to alert women to the likelihood of carrying a baby with irreversible genetic diseases. Some of their main advantages are their low cost, ease of performance, and the possibility of obtaining results quickly. Although they don’t confirm, they do provide a good deal of guidance and reserve the practice of more complex studies for those mothers who have a proven high risk.

First of all, it should be noted that invasive confirmatory tests carry other risks, such as miscarriages or infections. For this reason, the ultimate decision to perform them is the mother’s and none of them is strictly obligatory.

What’s essential is that the pregnant woman is duly informed of the condition that her baby may present, of the risks of the diagnostic procedures, and of her rights and obligations to terminate the pregnancy, should she wish to do so.

From the beginning of gestation, doctors begin to evaluate some aspects of the baby that may suggest the possibility of genetic diseases. One of the strategies implemented for this purpose is the triple screening or tripel test.

This study seeks to establish the risk of the baby having Down syndrome, Edwards’ syndrome, or Patau’s syndrome. Are you interested in learning more about this prenatal test? Keep reading, we’ll tell you all about it below.

What does the triple screening consist of?

As we’ve already mentioned, the triple screening or triple test is a routine complementary test in the first trimester of gestation.

The objective of this test is to establish the mathematical probability that the baby being born has one of the most frequent genetic diseases: Down syndrome (trisomy 21), Edwards’ syndrome (trisomy 18), or Patau’s syndrome (trisomy 13). It also evaluates the presence of defects in the neural tube, which is the precursor structure of the brain and other organs of the nervous system.

This screening combines three different strategies:

- Ultrasound study of the baby. Specifically, the measurement of the nuchal fold or nuchal translucency study.

- The determination of specific biochemical markers in maternal blood.

- Analysis of the mother’s demographic data, such as age, weight, and ethnicity, among others.

Once the information has been collected, the physician enters the data into a computer to determine a percentage risk of suffering from the aforementioned diseases. In other words, it doesn’t make a diagnosis of certainty of any of them, but rather alerts about the high or low probability of having them.

Although this test isn’t conclusive, its results are quite indicative. In the case of Down syndrome, the test is accurate in more than 95% of cases and its false positive rate is 4%. In other words, up to 4 out of every 100 fetuses considered to be at risk for the disease don’t have it in the end.

For this reason, when faced with a report of a high risk of fetal genetic disease, the physician proceeds to perform a confirmatory and invasive study, such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling. Both tests have a degree of diagnostic certainty of 99%.

When is the triple screening performed?

The triple screening is indicated between 11 and 14 weeks of gestation because this is the optimal period of reliability. Although it can be performed beyond the 15th week, it’s important to know that the diagnostic sensitivity decreases considerably with time.

All women, regardless of their history, are candidates for this study.

What is assessed in each test of the triple screening?

Here, we’ll tell you what is analyzed in each of the screening tests and how so that you can understand why they are so important.

1. Determination of biochemical markers in maternal blood

Through a maternal blood sample, specialists analyze the values of some hormones that may suggest an alteration in the number and distribution of the baby’s chromosomes. For example, alpha-fetoprotein (PAPP-A), human chorionic gonadotropin (free beta-HCG), and estriol. In some cases, inhibin A is also assessed and the study is called a quadruple test.

When there’s a genetic problem, these hormones tend to be altered. In Down syndrome, PAPP-A tends to be decreased and beta HCG elevated.

2. Abdominal ultrasound with measurement of the fetal nuchal fold

The second component of the combined screening is to evaluate the nuchal translucency, which is a fluid space at the back of the baby’s head. In general, in babies who have a genetic abnormality, this tends to be thicker than in those who do not.

In addition, the specialist will measure the length of the baby, which is indicated as the cranial-caudal length (CRL).

3. Analysis of maternal demographic data

The two parameters mentioned above are “crossed” in a computer along with certain information about the mother: Her age, her weight, the number of fetuses she’s carrying, her race, and her pathological history, among others.

It should be noted that not all women have the same degree of risk of carrying a fetus with a genetic disease. Below, we’ll tell you who is more likely to have a baby with these conditions:

- Women over 35 years of age.

- People with a family history of Down, Edwards, or Patau syndrome and other genetic anomalies.

- Pregnant women with a history of miscarriages or babies with congenital malformations.

- Pregnant women who’ve been exposed to environmental factors that increase the risk of a genetic alteration, such as exposure to ionizing radiation.

How are the test results interpreted?

As we mentioned above, this test isn’t diagnostic, but rather establishes the risk or probability of suffering from some specific diseases. Therefore, the results are indicated with a numerical value (as a fraction) and not with a “positive” or “negative”, as with other evaluations.

For example, if the result is 1/750 or 1:750, it means that the chances of carrying a baby with Down, Edwards, or Patau syndrome are 1 in 750. If we took 750 women with similar baseline conditions and similar blood and ultrasound results, only one of them would give birth to a baby with one of these diseases.

Now, is this risk high or low? Is it worrisome or not? As you’ll see, the interpretation of the results can be somewhat confusing for a mother. Therefore, it’s best to discuss the reports with the specialist, who’ll be able to give you the explanation you need.

In general, laboratories have established parameters to define high, moderate, or low risk and usually take into account the following values:

- Greater than 1/270 is considered a high risk.

- Between 1/270 and 1/1000 is considered an intermediate risk.

- Less than 1/1000 is considered a low risk.

If the pregnant woman receives a triple screening report with a high risk of fetal genetic disease (1/270; 1/150; 1/100…), an accurate diagnostic test, such as amniocentesis, should be performed.

Confirmatory testing

When screening is positive, it’s important to proceed with more specific, more complex, more costly, and more invasive evaluations:

- Fetal DNA test in maternal blood: Chorionic villus sampling: This procedure is performed when a detailed analysis of the baby’s DNA is required in order to detect other genetic diseases or to confirm/rule out the presence of Down’s, Edwards’, or Patau’s syndrome. This requires taking a blood sample from the mother and sending it to a specialized laboratory.

- Amniocentesis: This test is more invasive than the previous one and is reserved only for cases in which it’s justified, as it’s not risk-free. It consists of taking a sample of amniotic fluid through a puncture of the sac that houses the baby.

- Chorionic biopsy: Chorionic villus sampling: like the previous one, this is an invasive test and consists of taking a sample of the chorionic villi from the placenta. It’s performed by means of a puncture of the mother’s abdomen in order to study the baby’s DNA.

Some final considerations on prenatal studies

Screening tests are performed to alert women to the likelihood of carrying a baby with irreversible genetic diseases. Some of their main advantages are their low cost, ease of performance, and the possibility of obtaining results quickly. Although they don’t confirm, they do provide a good deal of guidance and reserve the practice of more complex studies for those mothers who have a proven high risk.

First of all, it should be noted that invasive confirmatory tests carry other risks, such as miscarriages or infections. For this reason, the ultimate decision to perform them is the mother’s and none of them is strictly obligatory.

What’s essential is that the pregnant woman is duly informed of the condition that her baby may present, of the risks of the diagnostic procedures, and of her rights and obligations to terminate the pregnancy, should she wish to do so.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Álvarez, F. (2003). Cribado prenatal sérico materno para la detección de anormalidades cromosómicas fetales: importancia clínica de la tasa de falsos positivos. Investigación clínica Vol.44 N° 3.

- Gerulewicz, D, et al. (2005). Pruebas bioquímicas en sangre materna para la identificación de fetos con riesgo de defectos cromosómicos y complicaciones asociadas al embarazo. Revista de Perinatología y Reproducción Humana Vol.19 N° 2. México. Recuperado de: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/lil-632269

- Quiroga, M. et al (2016). Diagnóstico prenatal de anomalías cromosómicas. Examen prenatal no invasivo. Revista peruana de ginecología y obstetricia. Vol.62 N°3. Recuperado de: http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2304-51322016000300008

- Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia (SEGO) (2012). Guía de práctica clínica: Diagnóstico prenatal de los defectos congénitos. Cribado de anomalías cromosómicas. Protocolos y Guías de Actuación Clínica en Ginecología y Obstetricia Vol 24. N°2. Recuperado de: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-diagnostico-prenatal-327-articulo-guia-practica-clinica-diagnostico-prenatal-S2173412712001059

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.