Calcified Placenta: What You Need to Know

Written and verified by the pediatrician Marcela Alejandra Caffulli

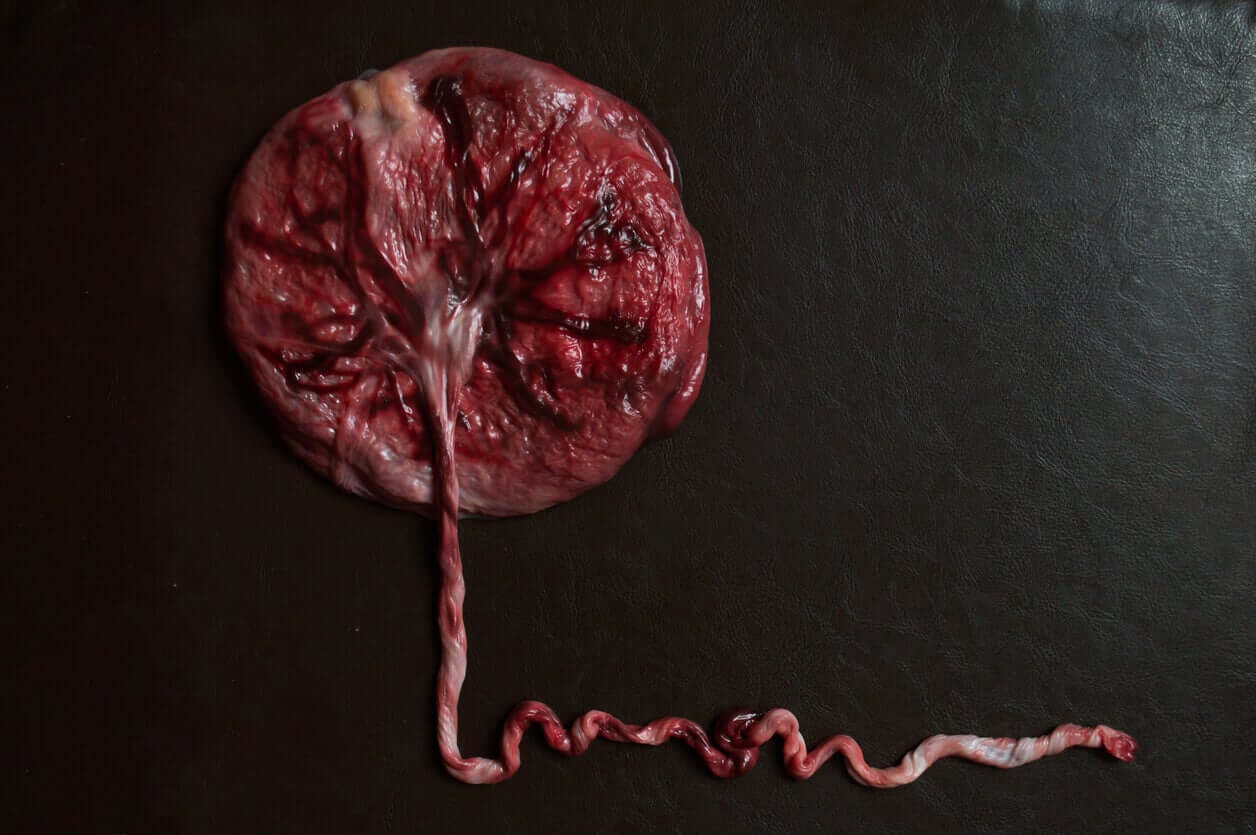

The placenta is an organ that forms during pregnancy and is responsible for providing oxygen and nutrients to the baby. Unlike other viscera, it has a limited life span and is believed to be “self-programmed” to degenerate towards the end of pregnancy. One of the most characteristic signs of aging is calcium deposits, which lead to the development of the calcified placenta.

Although this phenomenon is physiological, in some circumstances, it could suggest a risk situation for the mother or the baby. However, specialists find some controversy in this, as the evidence isn’t absolutely conclusive.

Today, we’re going to tell you everything you need to know about the calcified placenta, so that you can understand why it occurs and what it means to have it. Keep reading!

The physiological development of the placenta

As we’ve mentioned, the placenta is a fundamental structure for the growth of the fetus within the womb. Not only does it promote the exchange of gases and nutrients between the mother and the baby, but it also manufactures the hormones necessary for pregnancy to take place.

It’s an organ that develops together with the baby and that stops being functional when the pregnancy approaches term.

To form, the placenta depends on factors of the embryo (the future baby) and its mother. And ultimately, through this structure, both individuals will be fused.

The placental development process begins in the first week after conception, even before the embryo implants in the mother’s uterus. At this time, the blastocyst (200-cell embryonic stage) becomes polarized and develops an internal structure called a trophoblast. This will be in charge of implanting itself in the womb and in the future, developing the placenta.

At the same time, the uterine endometrium also makes some changes in its structure to accommodate new life. Among them, the modifications in the glands, in the blood vessels, and in the immune cells of this tissue stand out. This entire process is called decidualization and occurs before contact with the embryo.

Around the eighth day after conception, the blastocyst (embryo) adheres to the endometrium (uterus), and after a few days, penetrates it to its full thickness. From there, the interaction between the two will lead to the development of the different placental structures, until reaching the definitive stage around week 10.

A healthy and functional placenta results from the proper succession of events. But when this doesn’t occur in a coordinated way, abnormal structures may develop, capable of affecting the health of the mother, the baby, or both.

Aging of the placenta

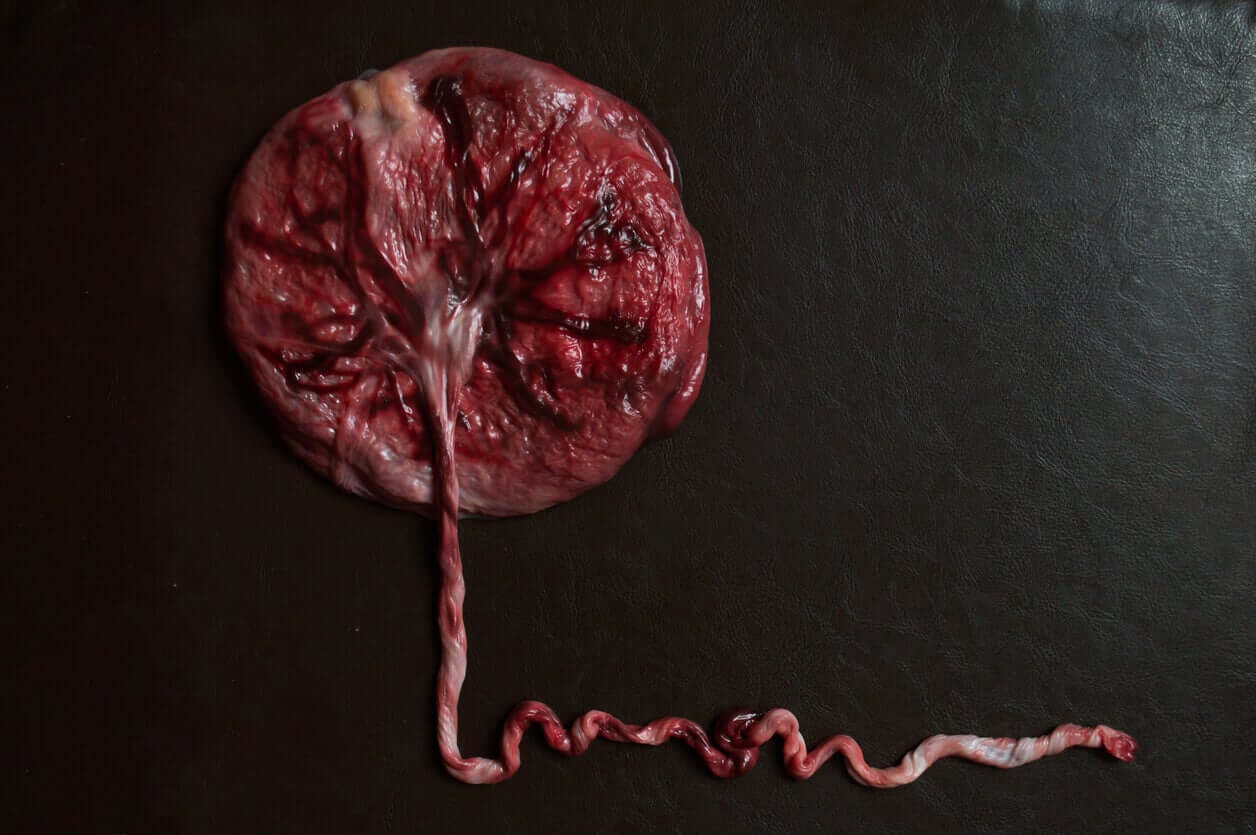

The placenta grows and matures rapidly until almost mid-pregnancy, and towards the end of the third trimester, it begins to show some signs of aging. Among them, physiological calcifications.

Around week 36, ultrasound scans of many women can detect some calcium hydroxyapatite deposits in the placental vessels. This is known as a calcified placenta.

It’s presumed that this phenomenon occurs as a consequence of an increase in the expression of growth factors typical of the end of pregnancy, as part of the natural self-degradation process.

However, calcifications can be seen at an earlier stage (before 34 weeks) and this is known as premature calcified placenta. In these cases, the deposits are produced by mechanisms other than physiological aging and are often associated with maternal or fetal illnesses.

In some cases, these deposits are produced by necrosis (death) of the placental tissues. Or after times, they occur due to an overload of calcium in the maternal blood, either due to excess intake by the woman or due to a disorder of the fetus when it comes to absorbing this mineral from the blood.

Calcified placenta: A pathological finding?

As we’ve mentioned, the calcification of the placenta can be understood as a normal event. This implies that many times it represents a simple finding of the ultrasound, without any repercussion on the health of the mother or baby.

The big question that experts are asking today is what relevance should be given to these deposits and what’s the follow-up that should be offered to pregnant women who present them. The evidence is quite controversial in this regard.

For several decades, obstetricians have had a subjective classification system for the degree of maturity of the placenta, developed by Grannum. The objective of using this tool is to determine which apparently healthy patients require closer follow-up.

But even in the highest grades of this classification, it’s not possible to assert the existence of a greater risk to the health of the mother and child. In fact, the association between these levels and gestational diseases (such as diabetes or hypertension) or newborns (such as low weight) hasn’t been demonstrated.

What’s been shown is that premature calcified placenta is associated with a higher risk of adverse fetal effects (such as intrauterine growth retardation), due to the lower blood supply it receives.

Causes of calcified placenta

Although the development of calcifications is closely linked to gestational age, there are other predisposing factors to developing it :

- Exposure to tobacco smoke (from an active or passive smoking mother)

- Maternal cardiovascular disease

- Excess calcium in the blood (due to kidney disease in the mother, due to excessive intake, or disorders in the baby’s metabolism)

- Maternal malnutrition

What should I do if I have a calcified placenta?

The diagnosis of this condition is through an ultrasound, as it doesn’t usually produce any symptoms in the mother. Many times, it’s also not associated with fetal illnesses or pregnancy complications.

So, if it’s detected in the last month (from week 36) and the baby grows normally, it’s most likely that no action is necessary.

However, if it’s detected prematurely and an insufficient blood supply to the fetus is found, the doctor is likely to consider ending the pregnancy. However, this is a decision that’s made only when the situation warrants it.

As we always mentioned, when in doubt, it’s best to talk to the professional who’s following your pregnancy. Only then can you make the best decisions to preserve your health and that of your little one.

The placenta is an organ that forms during pregnancy and is responsible for providing oxygen and nutrients to the baby. Unlike other viscera, it has a limited life span and is believed to be “self-programmed” to degenerate towards the end of pregnancy. One of the most characteristic signs of aging is calcium deposits, which lead to the development of the calcified placenta.

Although this phenomenon is physiological, in some circumstances, it could suggest a risk situation for the mother or the baby. However, specialists find some controversy in this, as the evidence isn’t absolutely conclusive.

Today, we’re going to tell you everything you need to know about the calcified placenta, so that you can understand why it occurs and what it means to have it. Keep reading!

The physiological development of the placenta

As we’ve mentioned, the placenta is a fundamental structure for the growth of the fetus within the womb. Not only does it promote the exchange of gases and nutrients between the mother and the baby, but it also manufactures the hormones necessary for pregnancy to take place.

It’s an organ that develops together with the baby and that stops being functional when the pregnancy approaches term.

To form, the placenta depends on factors of the embryo (the future baby) and its mother. And ultimately, through this structure, both individuals will be fused.

The placental development process begins in the first week after conception, even before the embryo implants in the mother’s uterus. At this time, the blastocyst (200-cell embryonic stage) becomes polarized and develops an internal structure called a trophoblast. This will be in charge of implanting itself in the womb and in the future, developing the placenta.

At the same time, the uterine endometrium also makes some changes in its structure to accommodate new life. Among them, the modifications in the glands, in the blood vessels, and in the immune cells of this tissue stand out. This entire process is called decidualization and occurs before contact with the embryo.

Around the eighth day after conception, the blastocyst (embryo) adheres to the endometrium (uterus), and after a few days, penetrates it to its full thickness. From there, the interaction between the two will lead to the development of the different placental structures, until reaching the definitive stage around week 10.

A healthy and functional placenta results from the proper succession of events. But when this doesn’t occur in a coordinated way, abnormal structures may develop, capable of affecting the health of the mother, the baby, or both.

Aging of the placenta

The placenta grows and matures rapidly until almost mid-pregnancy, and towards the end of the third trimester, it begins to show some signs of aging. Among them, physiological calcifications.

Around week 36, ultrasound scans of many women can detect some calcium hydroxyapatite deposits in the placental vessels. This is known as a calcified placenta.

It’s presumed that this phenomenon occurs as a consequence of an increase in the expression of growth factors typical of the end of pregnancy, as part of the natural self-degradation process.

However, calcifications can be seen at an earlier stage (before 34 weeks) and this is known as premature calcified placenta. In these cases, the deposits are produced by mechanisms other than physiological aging and are often associated with maternal or fetal illnesses.

In some cases, these deposits are produced by necrosis (death) of the placental tissues. Or after times, they occur due to an overload of calcium in the maternal blood, either due to excess intake by the woman or due to a disorder of the fetus when it comes to absorbing this mineral from the blood.

Calcified placenta: A pathological finding?

As we’ve mentioned, the calcification of the placenta can be understood as a normal event. This implies that many times it represents a simple finding of the ultrasound, without any repercussion on the health of the mother or baby.

The big question that experts are asking today is what relevance should be given to these deposits and what’s the follow-up that should be offered to pregnant women who present them. The evidence is quite controversial in this regard.

For several decades, obstetricians have had a subjective classification system for the degree of maturity of the placenta, developed by Grannum. The objective of using this tool is to determine which apparently healthy patients require closer follow-up.

But even in the highest grades of this classification, it’s not possible to assert the existence of a greater risk to the health of the mother and child. In fact, the association between these levels and gestational diseases (such as diabetes or hypertension) or newborns (such as low weight) hasn’t been demonstrated.

What’s been shown is that premature calcified placenta is associated with a higher risk of adverse fetal effects (such as intrauterine growth retardation), due to the lower blood supply it receives.

Causes of calcified placenta

Although the development of calcifications is closely linked to gestational age, there are other predisposing factors to developing it :

- Exposure to tobacco smoke (from an active or passive smoking mother)

- Maternal cardiovascular disease

- Excess calcium in the blood (due to kidney disease in the mother, due to excessive intake, or disorders in the baby’s metabolism)

- Maternal malnutrition

What should I do if I have a calcified placenta?

The diagnosis of this condition is through an ultrasound, as it doesn’t usually produce any symptoms in the mother. Many times, it’s also not associated with fetal illnesses or pregnancy complications.

So, if it’s detected in the last month (from week 36) and the baby grows normally, it’s most likely that no action is necessary.

However, if it’s detected prematurely and an insufficient blood supply to the fetus is found, the doctor is likely to consider ending the pregnancy. However, this is a decision that’s made only when the situation warrants it.

As we always mentioned, when in doubt, it’s best to talk to the professional who’s following your pregnancy. Only then can you make the best decisions to preserve your health and that of your little one.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Salvatore Andrea Mastrolia, Adi Yehuda Weintraub, Yael Sciaky-Tamir, Dan Tirosh, Giuseppe Loverro & Reli Hershkovitz (2016) Placental calcifications: a clue for the identification of high-risk fetuses in the low-risk pregnant population?, The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 29:6, 921-927, DOI: 10.3109/14767058.2015.1023709. Disponible en: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25777792/

- Jamal A, Moshfeghi M, Moshfeghi S, Mohammadi N, Zarean E, Jahangiri N. Is preterm placental calcification related to adverse maternal and foetal outcome? J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017 Jul;37(5):605-609. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2017.1285871. Epub 2017 May 3. PMID: 28467149. Disponible en: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28467149/

- Wallingford MC, Benson C, Chavkin NW, Chin MT, Frasch MG. Placental Vascular Calcification and Cardiovascular Health: It Is Time to Determine How Much of Maternal and Offspring Health Is Written in Stone. Front Physiol. 2018 Aug 7;9:1044. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01044. PMID: 30131710; PMCID: PMC6090024. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6090024/#!po=10.9375

- Apaza Valencia John. Desarrollo placentario temprano: aspectos fisiopatológicos. Rev. peru. ginecol. obstet. [Internet]. 2014 Abr [citado 2021 Nov 09] ; 60( 2 ): 131-140. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2304-51322014000200006&lng=es. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2304-51322014000200006

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.